Sometime ago I made a personal project out of reading the list of Hugo award winning science fiction novels. I don’t remember exactly when it started, but as I write this I’m working my way through the 1990s. I offered to put together a reading list for friends based on the entries I’ve read so far with some light commentary on which ones I’d recommend and which ones I’d skip.

Me as a reader & Who this is for

I’m going to qualify this entire list with the kind of reader I am. First off, I tend to read short fiction and novellas. Shorter is better and I am immediately skeptical of any book over 250 pages. I also distrust books that are meant to be a series. Concise is good. I do not, however, have any particular preferences on hard science fiction versus “softer” science fiction. If you’re not familiar with the distinction then don’t even worry about it.

If you are willing to tell a stranger that you enjoy Gravity’s Rainbow, Finnegans Wake, or Foucault’s Pendulum then you’re almost certainly going to disagree with me a lot (I would gladly throw all three in the trash). No amount of flowery prose, structural innovation, or avant garde storytelling can make up for a lack of compelling plot or a point.

The award itself

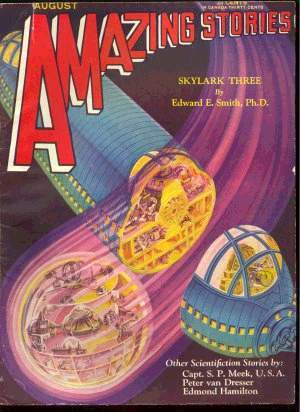

Named for Hugo Gernsbeck the founder of the first Science Fiction magazine Amazing Stories in 1926. The award itself is handed out annually at Worldcon, the World Science Fiction Convention, and is overseen by the World Science Fiction Society. Any dues paying member can make a nomination, and after nominations, vote. There ‘s no additional criteria like a book must be at least this sciency to win an award.

This is to say that the award, in many ways, is a popularity contest among the World Science Fiction Society members. As such, the award shouldn’t be construed as the “best” available, but rather the most popular. The social mores of the time and the makeup of the society itself are unavoidable. For example, science fiction had women writers for decades and was even started by Mary Shelly… but the first winner in 1953, The Demolished Man, is profoundly sexist.

So take any given work, especially the earlier works with a healthy grain of salt.

The List (1953-1963)

1953- The Demolished Man by Alfred Bester

The Demolished Man is a super fun inverted detective story told from the perspective of the guy doing the crime. The catch is that by the time of the book some humans have developed ESP. Not everyone, but enough that they’ve formed a world-wide guild and the police have mind readers available. So how do you commit a murder when the state can read your thoughts?

It’s a fun adventure but unless you like the almost cartoony-ness of the old pulp science fiction magazines this one might be rough. One critical summary included that the characters and their motivations only make sense in terms of Freudian psychology. And on the overt sexism, to borrow Jo Walton’s quote: “The words girl and pretty always come as a pair.”

As far as I know this is also the first appearance of the term “esper” from “ESP-er.” It also makes a number of jokes that literally only make sense in print. So that ‘s fun.

Recommendation: Read, but only if you like pulpy storytelling.

1954 (Retro Hugo)- Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

There was no Worldcon held in 1954 so this one was awarded in 2004 retroactively. The thing about retroactive awards like this is they go to the most popular book from the year that people remember, and given that many high schools teach this book, it’s no wonder it won.

Recommendation: Read because it’s a staple.

1955- They’d Rather Be Right (Also known as The Forever Machine) by Mark

Clifton and Frank Riley

Scientists develop a machine that they can feed facts into, and based on those facts, make “correct” deductions. This machine, named Bossy, is eventually able to be hooked up to human brains to “optimize” away false notions and bad information. This includes the fundamentals of how we age (aging is just a misconception of the body?) and thus confers immortality. The catch, is that it works like therapy. It can only “optimize” away this bad information if you’re willing to accept a better, rational understanding of everything in your head. Faced with the choice of immortality or acknowledging a lifetime built on potential falsehoods … most people would rather be right.

Many analyses of the award winners conclude that this is one of the worst works to ever actually win the award. It has very little in the way of development, and when it actually reaches the point where the point goes, it doesn ‘t actually make one. It has a handful of interesting questions, but none of them are explored in the work itself. It’s a massive setup with no delivery. On the other hand, it’s so short that it’s usually collected in anthologies, so you’re likely to get other, better stories along with it.

I will say, one of the things I do like about this book is their portrayal of scientists and academics as being human and developing religious-like attachment to their theories and works. It shows that science isn’t an infallible process, but rather a human one.

Recommendation: Skip, unless it comes in a good anthology.

1956- Double Star by Robert Heinlein

A down-on-his-luck actor going by the name The Great Lorenzo gets sucked into a massive political plot spanning Earth and Mars when he’s hired to be a body double for an unspecified individual. He winds up in a massive political plot that could lead to war. Hijinks ensue. This is a book strongly propelled by tension and to talk any more plot would ruin it.

I thoroughly enjoyed this book and would strongly recommend it. Especially if you ‘ve read other of Heinlein’s books. Also, this is one of the best first-person perspective books I’ve ever read, period. Heinlein does an amazing job of getting you into Lorenzo’s head. At 170 pages, the pacing is superb.

Recommendation: Definite read.

1957- No Worldcon Held

1958- The Big Time by Fritz Leiber

There’s a war called the Change War. It’s a war fought in the timeline, constantly rewriting events and modifying history. Outside of this timeline is The Big Time, which has a recuperation station for warriors coming back from battle where the story takes place. In contrast, there’s the Little Time where all the changes happen. The story is told from the perspective of a worker at the recuperation station talking to people engaged in the battles.

This book… is. so. boring. It suffers from the problem of existing in a world far more interesting than anything covered in the book. It’s the science fiction version of My Dinner With Andre. But dryer. It’s people sitting around talking about what happens in the world. On the positive side, it deals with more postmodern ideas like the mutability of history. On the other hand, so many better works have come along since this one I can ‘t recommend it. It’s only 130 pages… but it feels so much longer.

Update: Actually, feel free to skip anything by Fritz Leiber. I have yet to read anything of his I haven’t wanted to throw across the room.

Recommendation: Hard pass.

1959- A Case of Conscience by James Blish

A Peruvian Jesuit priest, Father Ramon Ruiz-Sanchez, is part of a survey team to the planet Lithia to investigate whether it should be brought into trade agreements. The Lithians, a lizard like people, have developed a perfect, innate, and infallible sense of morality without any notion of God or religion. Father Ruiz-Sanchez experiences something along a crisis of faith and the book explores religion’s impact on society.

It’s a surprisingly good example of hard science fiction told with a spiritual side. Regarding the science for instance, the name Lithia comes from the lithium content in the high concentration of pegmatite on the planet’s surface. Also be prepared to have a solid explanation of The Manichean Heresy.

Recommendation: Read.

1960- Starship Troopers by Robert A. Heinlein

The story of the space marine Juan “Johnny” Rico and his deployments first against “The skinnies” and then his subsequent deployment in The Bug War. This was the last of Heinlein’s “juvenile” novels and spends a healthy amount of time discussing civics, the military, voting, and the like. It’s also the origin of the term “space marine.”

If you’ve seen the 1997 movie of the same name you should know that the movie is a satirization of the book. The stories are essentially the same but where the movie is portraying a silly, comically pro-military propaganda machine, the book is quite serious in its treatment of the same ethics and ideology. Heinlein spent the rest of his career being accused of militarism and fascism for this book. That being said, I did enjoy it.

Recommendation: Read. Especially for the origins of the Space Marine trope.

1961- A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M. Miller, Jr.

The world is annihilated in a nuclear war called The Flame Deluge. One thousand years later humanity is finally starting to rebuild after a period referred to as The Simplification. Latin is once again common and the Catholic church reigns supreme. On a mission in the desert, a young novitiate of the church named Brother Francis Gerard discovers a bomb shelter owned by the same man credited with founding his order, Leibowitz. This sets off a 1500 year chain of events told in three beautiful vignettes. Themes include the cyclical nature of history, science, power, and religion.

This book is absolutely superb and I strongly recommend it.

Recommendation: Must Read.

1962- Stranger in a Strange Land by Robert A. Heinlein

The tale of the first human, Valentine Michael Smith, to grow up among Heinlein’s famous Martian aliens. Smith returns to Earth as a young adult having been raised by the Martians. He’s never experienced human cultures, television, politics, or the opposite sex. He makes his way through human society (and religion) as one of the most famous humans in history with an almost unfathomable claim to Mars itself (because of legal quirks in this universe).

Here’s a book where I openly acknowledge that I diverge from popular opinion. Despite its extreme popularity, I found this book almost unreadably boring. I’ve met numerous people that described it as “life changing” but I just don’t get it. Some of the “edgiest” content is about open relationships and polyamory, so if you’re already familiar with those subjects, this book isn’t going to come across as transgressive or edgy. It’s actually made the top of numerous “Best of the Banned Books” list for this reason.

Recommendation: Read, but only if you’re out of alternatives and want to see what the fuss is about.

1963- The Man in the High Castle by Phillip K. Dick

An alternate history set in 1962 presupposing that both Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan won World War II. Adventure in the carved up United States starting in San Francisco with a sprinkling of the I Ching. I would write more about it, but honestly, I really can’t stand Phillip K. Dick’s novels. I find his short stories superb, but most of his novel length works I just can’t get behind. Especially works like this that take on a 4th-wall-breaking meta- narrative. I also find his longer writing style incredibly boring.

Recommendation: Hard pass unless you know you like Phillip K. Dick novels.